Editing the Frederick Law Olmsted Papers has been a continually fascinating enterprise, in part because of the range of social, political and aesthetic issues addressed in Olmsted’s writings, and in part because of the existence on the ground today of scores of landscapes designed by Olmsted and his partners. Of special significance is his legacy of park planning, constituting some one hundred projects by Olmsted himself and nearly one thousand additional public parks, recreation areas, and scenic reservations planned by his sons after his retirement in 1895. This article focuses on efforts by the editors of the Olmsted Papers to assist in the revival and preservation of that legacy.

The Early Days

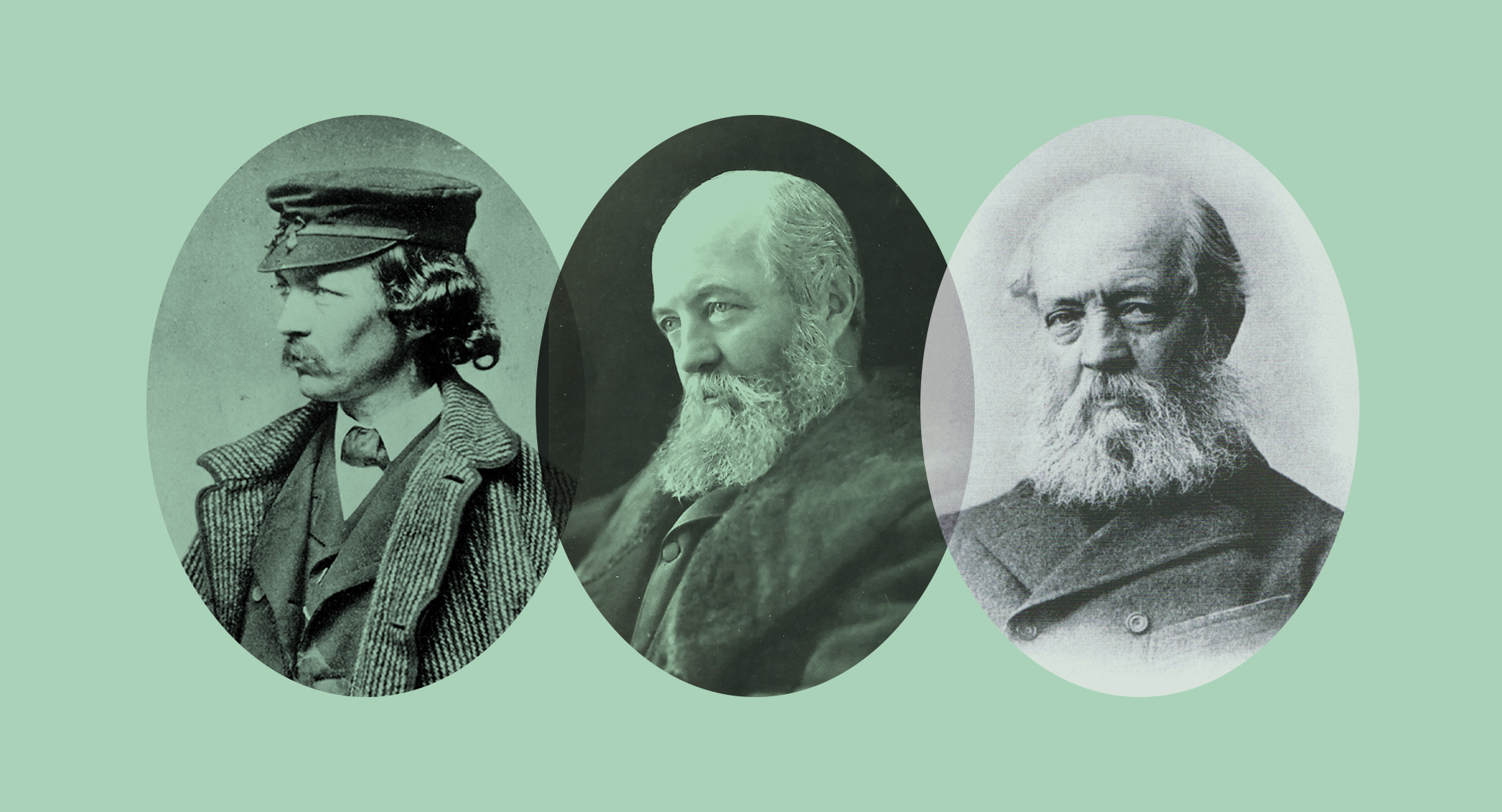

The editing of the Frederick Law Olmsted Papers series has coincided with a national revival of interest in Olmsted and his career as a landscape architect. This process began in 1972 with observances of the sesquicentennial of his birth that included articles in several national journals and major exhibitions at the National Gallery of Art in Washington and the Whitney Museum in New York. The following year saw the beginning of continuous funding of the Olmsted Papers project, under the editorship of Charles C. McLaughlin, by both the National Historical Publications and Records Commission and the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH). Soon thereafter, this funding began to be supplemented by grants from private foundations and individuals, most notably the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

By the time we published Volume 2 of the series, Slavery and the South, 1852-1857 (1980), dealing with Olmsted’s southern travels and involvement in the sectional controversies of the mid-1850s, and were beginning work on Volume 3, Creating Central Park, 1857-1861, a period of revival and restoration of Olmsted’s parks was underway. The first center of this activity was New York City, which has devoted many millions of dollars over the past two decades to master-planning and restoration in Olmsted’s major parks there – Central Park, Riverside Park, and Morningside Park in Manhattan, and Prospect Park and Fort Greene Park in Brooklyn. The appointment in 1979 of Elizabeth Barlow Rogers as administrator of Central Park provided a vital focus for activity in the first park that Olmsted designed, leading to the creation of the Central Park Conservancy, the best funded and most successful such public-private parks organization in the country.

Volume 3 of the Olmsted Papers (1983) provided the Central Park staff with Olmsted’s key documents concerning the design and construction of the park, as well as the most significant excerpts from other relevant documents written by Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, the co-designer of the park. The volume also provided ready reference to the nine “present condition” and “effect proposed” sketches that the designers submitted in the 1858 Central Park design competition, providing a visual supplement to the text of their proposal. In addition, the volume included a “tour” through Central Park during the first five years of its construction, the time that Olmsted had greatest control over the shape it would take.

The 63 photographs in this section, mostly stereographs taken in 1863, are a particularly valuable source for studying the “Olmsted idiom.” Indeed, the extensive private collection of photographs of Central Park from which this section was primarily taken, material from which the Olmsted Papers were the first to publish, has been a unique and frequently consulted source for the Central Park staff in the ensuing years. The photographs were accompanied in the volume by a plan of Central Park showing the position and direction of view of each of the photographs.

As for the other major Olmsted park in New York City, Prospect Park in Brooklyn, the Olmsted Papers editors have been closely associated with the restoration process there since the appointment of Tupper Thomas as administrator in 1980. We have met several times with the staff, reviewing plans for restoration of the Long Meadow, the Ravine, and the Woods, and guiding them to relevant documents and photographs. In the process there have been unexpected discoveries of material in the archives of the Olmsted National Historic Site in Brookline, MA, administered by the National Park Service.

At one point we discovered a dozen unidentified photographs that show, as we recognized, the original appearance of the Prospect Park site and early stages of construction. They were filed with photographs of Audubon Park in New Orleans, a 20th-century design by the firm. We also found the manuscript of a crucially important document concerning the “pastoral” landscape of the park’s Long Meadow section, which was rolled up with Olmsted’s plans of the mid-1870s for the street system of the 23rd and 24th wards (the Bronx). This 1868 document, “Address to the Prospect Park Scientific Association,” was published in Volume 1 of the Olmsted Papers Supplementary Series, Writings on Public Parks, Parkways, and Park Systems (1997), edited by Carolyn F. Hoffman and myself.

The Next Stage

The second major stage of the Olmsted parks revival took place in Massachusetts, where Olmsted moved from New York around 1880. In 1984 the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Management created the Olmsted Historic Landscape Preservation Program, which dedicated one million dollars to the development of historic landscape and structures reports, the collecting of copies of historic plans and photographs, and the preparation of long-term master plans, as well as to pilot construction projects in each of a dozen Olmsted-firm parks in the Commonwealth. Half of the parks selected were elements of Boston’s “Emerald Necklace,” while the others were in smaller cities throughout the state. I served as program-wide historical advisor, overseeing the work of a dozen landscape historians, while advising master planners on the Olmsted idiom and directing them to relevant visual and documentary materials in the historical record of other parks than the one for which they were responsible.

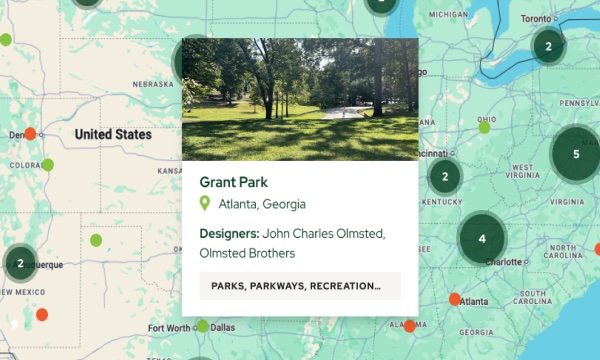

By the mid-1980s there was still no reliable listing of the design projects of Olmsted’s own career, or of the extensive work of the successor firm between 1895 and 1950 under the direction of his stepson and partner, John Charles Olmsted and his son, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. In 1987, the Olmsted Network, then known as the National Association for Olmsted Parks (NAOP), and the Massachusetts Association for Olmsted Parks (which had been very influential in the launching of the statewide Olmsted historic landscape program there) provided a grant to the Olmsted Papers, at a time when we needed additional private funds to continue payment of salaries, to create a national list of the work of the Olmsted firm. Drawing from the firm’s records in the possession of the National Park Service and the records we had compiled, Carolyn Hoffman and I prepared The Master List of Design Projects of the Olmsted Firm, 1857-1950, a compendium of 6,000 landscape commissions. This publication has been a valuable starting-point for inventory and restoration projects throughout the country and is now being installed as the first major element of the expanded website of the Olmsted National Historic Site: http://www.nps.gov/frla.

The master list project is one of several ways in which the editors have remained closely connected with the Olmsted Network, which we helped to found in 1980. There are also numerous state and city Olmsted associations that serve as regional extensions of the ON. These groups have been the vital center for Olmsted park restoration in Massachusetts, Maine, New York and Maryland, as well as Louisville, Atlanta and Seattle. The Olmsted Papers editors have addressed numerous national conferences of the organization and serve as advisors to several of the regional groups. In return, the ON is becoming an increasingly important source for funding of the Olmsted Papers project.

Centennial observances of Olmsted’s parks have also provided opportunity for the editors to promote restoration and preservation of Olmsted’s legacy. The first instance was the centennial of the Niagara Reservation, for which Olmsted was a leading campaigner, and for which he and Vaux prepared the overall plan in 1887. Commissioner Orin Lehmann of the New York State Department of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation asked me to organize a scholars’ symposium for the centennial of the day in 1885 that the state legislature established the Niagara Reservation. In addition, Vaux’s recent biographer Francis Kowsky and I prepared an exhibition and catalog, The Distinctive Charms of Niagara Scenery: Frederick Law Olmsted and the Niagara Reservation. These activities, and the attention they received from the press, led to formation of a citizens’ advisory group to oversee the administration of the reservation.

The centennial observances for Yosemite National Park came in 1990. Victoria Post Ranney, principal editor of Volume 5, The California Frontier, 1863-1865 (1990), and I both addressed the plenary session of the centennial conference. We emphasized the principles for managing the scenery of Yosemite that Olmsted set forth in his report of 1865 while serving as first chairman of the commission in charge of the original grant (consisting of Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Big Tree Grove). We also established a working relationship with the landscape architect at Yosemite, Don Fox. A further result of the centennial was the publication by the Yosemite Association of Olmsted’s report, using the text established by the Olmsted Papers and making it widely available at a time when a major debate concerning the future of that historic scenic resource is under way.

Other centennials have been those of the park systems of Rochester, NY, in 1988 and Louisville, KY, in 1991. Both led to ambitious master-planning and restoration programs costing several million dollars. For these programs the Olmsted Papers editors, in collaboration with other Olmsted scholars, were able to provide a full set of images of landscape plans and a set of significant historic photographs. We also assisted in preparation of transcriptions, arranged by topic, of the key design statements in the correspondence of the Olmsted firm. This approach appears to be the most effective way that the Olmsted Papers project has been able to promote long-term awareness of Olmsted’s design concepts on the part of those responsible for the ongoing maintenance of the parks, thereby securing the preservation of their distinctive historical character. In Louisville, continuing contact with the staff of Metroparks and the Louisville Olmsted Parks Conservancy provides a means for occasional review of the construction and planting that is taking placed based (at least in part) on the historical record that we provided.

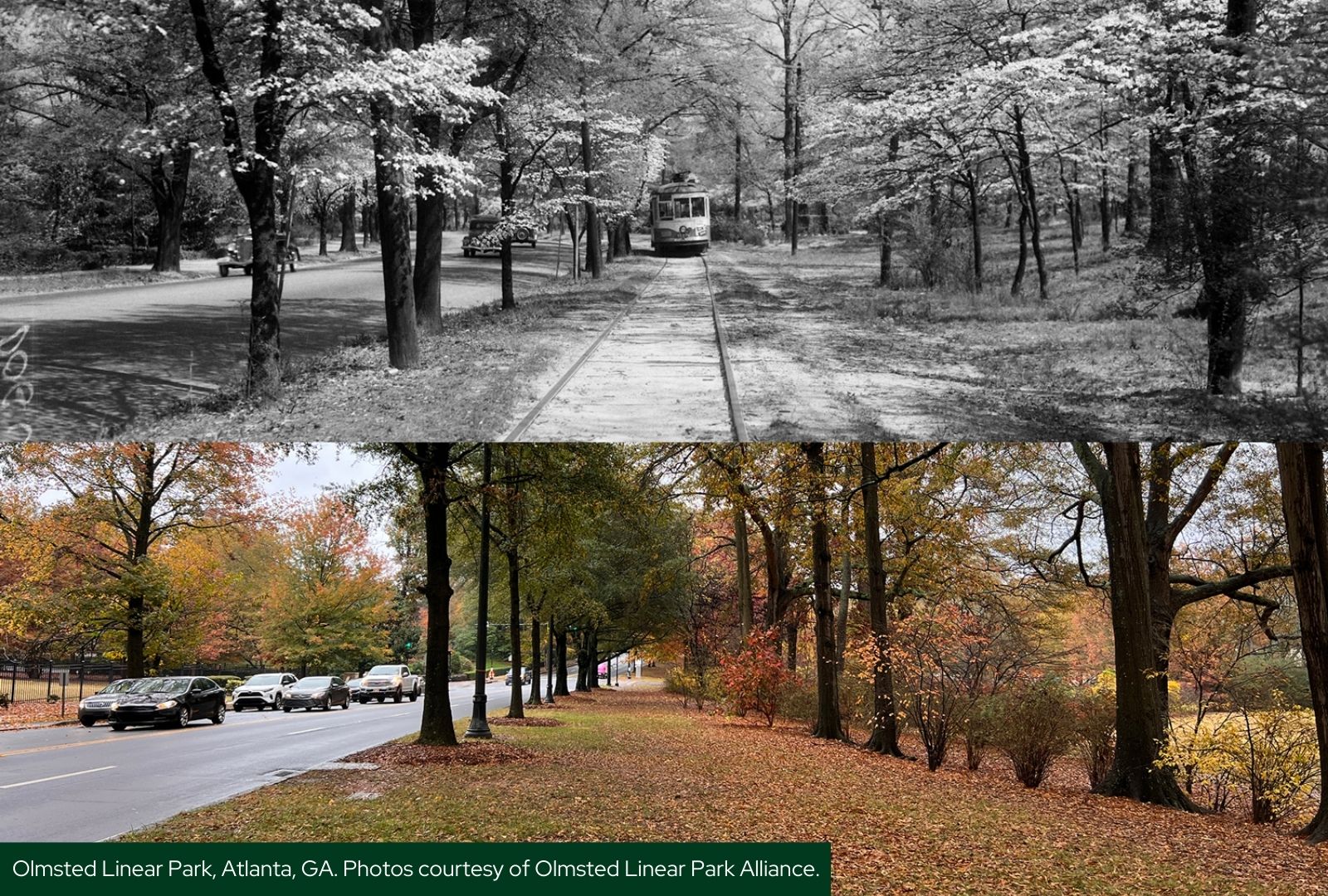

More recently, we have supplied the same kind of documentation — images of plans and photographs, copies of planting lists, and topically arranged excerpts of documents — to landscape architects engaged in work on the Midway Plaisance in Chicago, Patterson Park in Baltimore, Cadwalader Park in Trenton, NJ, and the linear parks of the Druid Hills section of Atlanta. For the city officials involved in restoration work on Olmsted’s park on Mount Royal in Montreal, we supplied on diskette the text of Olmsted’s eloquent report of 1881 and our transcription of forty letters that Olmsted wrote concerning the design and construction of the park. In this way, the material that we collect and organize in the process of preparing our selected letterpress edition is utilized by those responsible for planning the restoration and preservation of the Olmsted legacy of public design. The coinciding of the preparation of the Olmsted Papers series and the revival of concern for his parks has been a fortuitous one, giving the editors an opportunity for direct influence on the future of those landscapes that we would not otherwise have had.

Charles E. Beveridge is Series Editor of The Frederick Law Olmsted Papers.

Section of Boston’s “Emerald Necklace” (Boston Common to Franklin Park), 1894. Courtesy National Park Service, Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site.