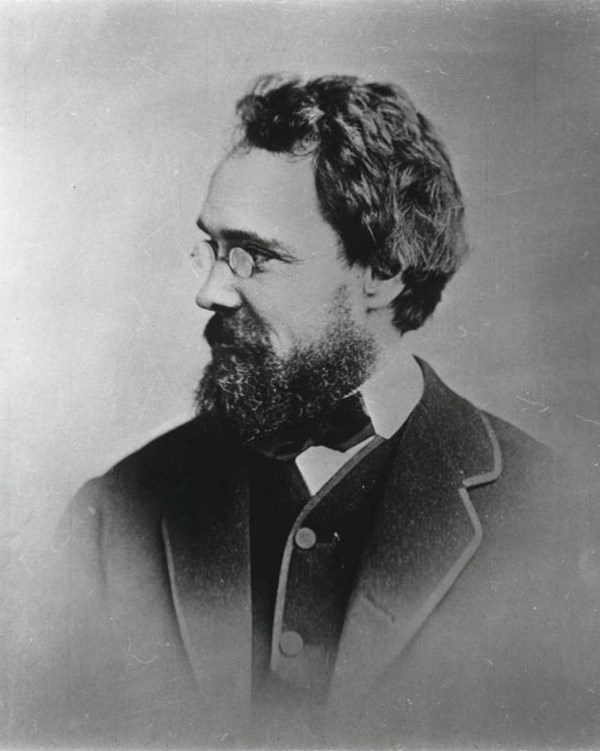

Calvert Vaux

By Francis R. Kowsky

Calvert Vaux (1828-1895) was born in London, where he studied architecture and landscape design before immigrating to America in 1850. He came at the invitation of Andrew Jackson Downing, America’s first nationally renowned spokesperson for the art of landscape architecture. Working with Downing in Newburg, NY, Vaux designed houses and grounds that capitalized on natural surroundings and scenic views. In 1851, Vaux assisted Downing in laying out the grounds between the White House and Capitol, the first significant public recreational landscape in America. After Downing’s death in 1852, Vaux continued to work in Newburgh before moving to New York in 1856. When the city purchased land for the new Central Park, Vaux worked behind the scenes to compel civic leaders to institute a competition for its design. In 1857, he asked Frederick Law Olmsted to join him in preparing an entry for the Central Park competition. Together they developed the winning Greensward plan that outlined a large “country park” in the heart of the metropolis.

While the park was being constructed, Olmsted left New York, first for Washington, where he became secretary of the United States Sanitary Commission, and then for California, where he managed the Mariposa Mining Estate. It took several years for Vaux to convince his friend to return East to join him in developing Brooklyn’s Prospect Park. In 1865, the reunited partners took up the design of Prospect Park, their most fully evolved example of pastoral landscape as urban park. Alfred Janson Bloor, who had worked in Vaux’s office and was a longtime observer of the New York architectural scene, wrote in 1903: “My impression is that Frederick Law Olmsted’s reputation richly deserved individual recognition and separate honor as regards landscape work… But my conviction on personal and in some degree on exclusive knowledge is that Calvert Vaux… was the sole designer of the guiding lines and main features of Prospect Park.”

Leading the nascent urban park movement, in 1868, Olmsted and Vaux prepared the initial proposal for parks and parkways in Buffalo. It was the first plan for an interconnected park system to be implemented by an American city. Other places that sought the partners’ advice during the years after the war were Albany, NY; Newark, NJ; and Chicago and Riverside, IL. The latter is regarded as the country’s first major suburban residential community.

Along with landscape projects with Olmsted, Vaux pursued a parallel career as an architect. He designed many houses that displayed sensitive rapport with nature, including the home and studio of the painter Jervis McEntee, who was his brother-in-law. Most of his early works of this type appeared in his book Villas and Cottages, which came out in 1857. Vaux was also responsible for bridges and other structures that embellished Central Park and other urban parks that he and Olmsted laid out. Bethesda Terrace in Central Park is his most well-known park structure. He also authored imaginative architectural features in Prospect Park and the Buffalo parks.

In the 1870s, Vaux prepared plans for some of the largest buildings North America had yet seen: the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the American Museum of Natural History, and a design for a vast exhibition hall for the Centennial Exposition at Philadelphia. Among his later clients for houses were the landscape painter Frederic Edwin Church, who actively participated in the plan of Olana at Hudson, NY; artist Worthington Whittredge at Summit, NJ; and reform politician Samuel Tilden on Gramercy Park in New York City (whose house is the present-day National Arts Club).

Dissolution of the Olmsted-Vaux Partnership

In 1872, Vaux and Olmsted dissolved their partnership of seven years. Over the next two decades, Olmsted assumed the position of America’s foremost landscape architect. Vaux, however, did not let the hurt and anger he felt at being forgotten as the co-designer of Central Park sever the connection with Olmsted. The two men stayed in touch even when, in the early 1880s, Olmsted left New York for Brookline, MA, where his office and home, Fairsted (the present Fredrick Law Olmsted National Historic Site), became the vital center of the landscape architecture profession in America. Vaux remained in New York and, with diminishing success, continued to practice architecture. In the 1880s and early 1890s, he also served as landscape architect to the New York Department of Parks. During this period, he fought many difficult battles to preserve Central Park from changes and intrusions incompatible with the ideals of the Greensward plan.

Later Collaborations

Even though they had gone separate ways, Vaux and Olmsted worked together on special projects. In 1885, the State of New York purchased the area on the American side of Niagara Falls to create a free public park. Two years later, Olmsted and Vaux prepared a master plan that restored and preserved Niagara’s magnificent scenery while making it accessible to thousands of tourists. In 1889, the two men agreed to donate their services to the city of Newburgh to lay out a park there in memory of Andrew Jackson Downing.

In 1895, a significant chapter in American art came to an end. In that year, Vaux died in New York and Olmsted, suffering from mental illness, retired from active practice in Brookline. Many years before, Vaux had admonished his new friend that God had destined him to be a landscape architect: “He cannot have anything nobler in store for you,” he said. Indeed, Olmsted, who believed that Vaux was unsurpassed in solving “problems of planning for convenience,” admitted that had it not been for Vaux, “I should have not been a landscape architect. I should have been a farmer.” Together these two men of genius had elevated the practice of landscape architecture to the status of a true profession and changed the quality of life in America’s cities.

Sources:

Francis R. Kowsky, Country, Park and City: The Architecture and Life of Calvert Vaux (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998).