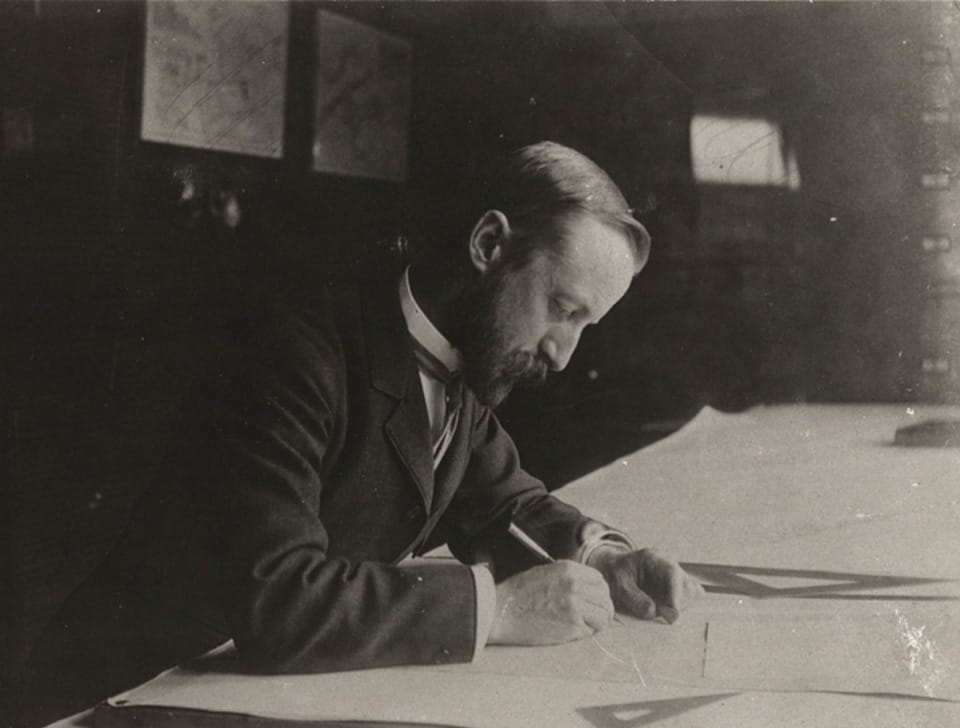

John Charles Olmsted

A landscape architect and planner.

By Arleyn Levee

John Charles Olmsted

The early life of John Charles Olmsted (1852-1920) was filled with extraordinary and traumatic events that were important in forming his shy personality and his broad-ranging interests. He was born in Vandeuvre, near Geneva, Switzerland, son of Dr. John Hull Olmsted and Mary Cleveland Perkins Olmsted. By the time he was five, John Charles had traversed the Atlantic twice, lost his father to tuberculosis, gained a stepfather in 1859 (his uncle, Frederick Law Olmsted), and settled down to a more orderly life, in a house in the middle of Central Park, then under construction.

The cozy stability of this situation was soon interrupted, first by the Civil War, when his stepfather transferred his new family to Washington, D.C., in 1862, and then by a move to the Mariposa Estate, a frontier gold-mining operation in the foothills of California’s Sierra Nevada, which the senior Olmsted managed from 1863 until 1865. Education amid the scenic splendors of Yosemite and the giant sequoias taught John Charles to read the landscape by its flora and fauna, its fossils and minerals.

These lessons were reinforced in the summers of 1869 and 1871 when he returned to the frontier, this time as a member of Clarence King’s survey party in Nevada and Utah along the 40th Parallel. Here, under often dangerous conditions, he developed his visual memory to record with speed the topographical, geological and botanical clues of the land, skills that proved invaluable in his later work.

Early Practice in New York

Following his graduation from Yale’s Sheffield Scientific School, Olmsted began his professional career as an apprentice in his stepfather’s New York office. Early projects included work on the U.S. Capitol grounds and several park and institutional projects. Travel to Europe in 1877–1878 with concentrated architectural study in London broadened his vision and further refined his skills. By 1884, with the move of the firm to Brookline, MA, John Charles had become a full partner with his stepfather. The firm soon grew to include Henry S. Codman and Charles Eliot as co-partners. After Frederick Law Olmsted’s retirement and the deaths of Codman and Eliot, John Charles and his younger half-brother, Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. formed Olmsted Brothers in 1898. John Charles was senior partner until his own death in 1920; the firm continued until 1950.

In addition to his extensive design and planning work, John Charles took responsibility for developing productive office and training procedures to manage a growing staff and diverse national practice. As one of the trainees, later a friend and collaborator, Arthur Shurcliff, recalled, Olmsted was a “man of few words, fond of detail,… [with] a broad grasp of large scale landscape planning” who “carried to completion a vast amount of work quietly with remarkable efficiency.” Other apprentices, later colleagues, praised his teaching and thoughtful advice; they admired his ability to resolve complex design problems with artistry and practicality while enhancing and protecting the natural features of a site.

Professional Memberships

Like his stepfather, Olmsted was committed to the development of landscape art as a profession and to the education of communities and clients about the long-term benefits to be gained from careful, comprehensive planning. To this end he was generous with his time and skills to organizations that sought to extend the influence of sound landscape planning to beautify burgeoning cities. He was a founding member of the American Society of Landscape Architects, serving as its first president and establishing the standards of membership, while being active in other groups such as the American Park and Outdoor Art Association (later the American Civic Association) and the American Association of Park Superintendents, which brought together various professionals and civic leaders.

Design Philosophy and Major Projects

Although Olmsted’s published writings are few, his extensive professional correspondence and reports reveal his comprehensive philosophy of design, innovative yet pragmatic; reflective of the aesthetic tenets of his stepfather, yet responsive to the new social, economic and political demands of 20th-century cities. His advice to clients, whether for public, private or institutional projects, was to plan for the future, to acquire as much land as possible to enable a cohesive design, protecting scenery and yet fulfilling the functional requirements.

This advice was critical for municipalities for whom the firm was designing city-shaping park and parkway systems. As Olmsted noted, “the liberal provision of parks in a city is one of the surest manifestations of the…degree of civilization, and progressiveness of its citizens. As in the case of almost every complex work composed of varied units, economy, efficiency, symmetry and completeness are likely to be secured when the system as a whole is planned comprehensively and the purposes to be accomplished defined clearly in advance.”

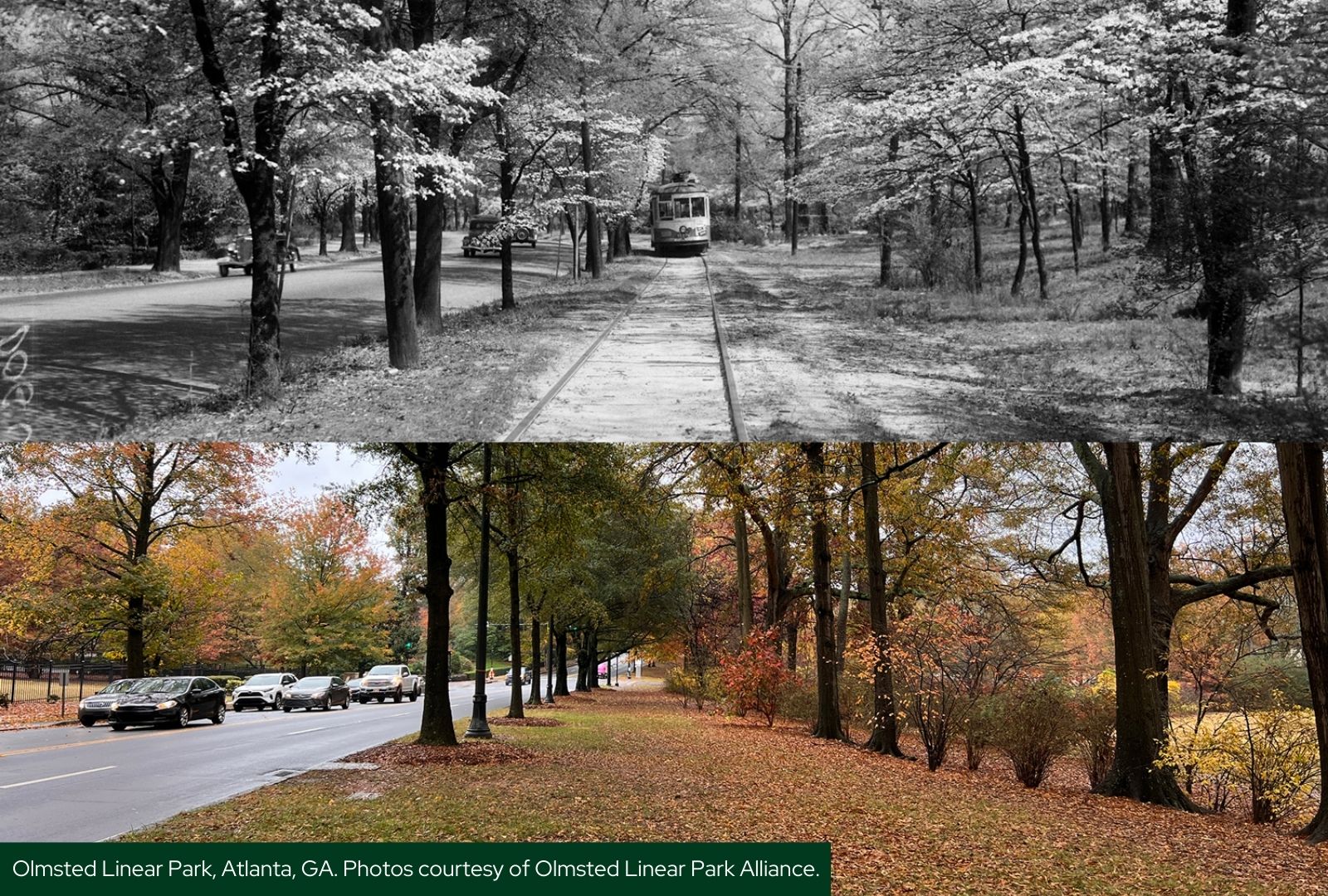

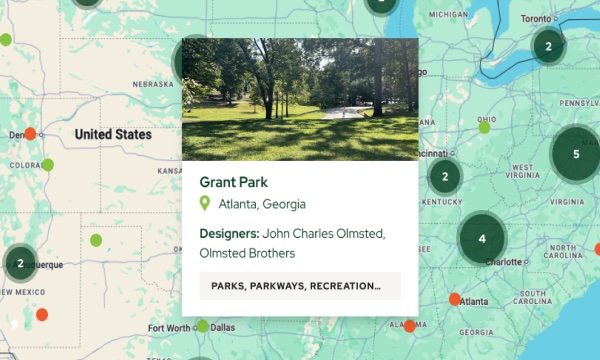

On the basis of this philosophy, Olmsted continued the park planning begun by his stepfather for Boston, Buffalo, Detroit, Rochester, Atlanta, Hartford, Louisville, Brooklyn, Chicago and other cities. He developed park systems for municipalities in diverse locations, including Portland, ME, and Portland, OR, Seattle and Spokane, Dayton and Charleston, and countywide parks and parkways for Essex County, NJ. In New Orleans and Watertown, NY, he designed individual parks of great originality on difficult sites. For the small parks in Chicago’s densely populated industrial south side, he turned derelict land parcels into an imaginative and efficient network of playgrounds to serve immigrant families. Park design in cities led to commissions for numerous institutions and subdivisions, often including individual residential work, large and small.

Much of the fabric and amenity of cities such as Louisville, Dayton, Seattle and northwest Washington, D.C., results from the extensive planning for residential areas which Olmsted originated, with its associated roads, greenspaces, schools and business areas. Comprehensive planning for communities around industrial plants, as in Depew, NY, and Vandergrift, PA, or around the National Cash Register factory in Dayton, created attractive neighborhoods instead of bleak tenements. Olmsted’s abiding architectural interest was reflected in his residential work, where he took special care to accommodate building to site and vistas, often making preliminary house designs and collaborating closely with the residential architect.

Likewise, plans for many park structures, particularly in the Boston system, originated with his sketches. Working cooperatively with architects was a major component of his institutional planning for school campuses, sanatoriums, state capitols and civic buildings across the country. His landscape layout provided a remarkably perceptive guide for future building development, retaining some degree of natural beauty in the site. Exposition planning, beginning with his work for the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair and continuing with the 1906 Lewis and Clark Exposition in Portland, OR, and the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, which shaped the University of Washington campus in Seattle, continued his architectural collaboration. He terminated the firm’s work for the San Diego Exposition of 1915 when he felt that the architectural and business plans violated the landscape integrity of Balboa Park.

Later Career

For over 40 years, John Charles Olmsted was a respected leader in the landscape and early planning professions, leaving a profound mark on the land, often unrecognized today. The firm’s clientele grew to more than 3,500 commissions by the time of his death, many of which he had originated. An indefatigable worker, he was slowed in his last years of practice by the cancer that eventually took his life. In his remarkable career, Olmsted bridged the centuries from the vanishing frontier to the 20th-century urban realities, leaving a lasting legacy of public and private designs across the country which melded a picturesque aesthetic and pragmatic planning.

Sources:

Olmsted Brothers [John Charles Olmsted]. “Report of Olmsted Brothers.” In First Annual Report of the Board of Park Commissioners, 1884–1904. Seattle, 1905, 43–85. Like reports for numerous other cities where John Charles Olmsted developed park system plans, it contains an overview of his ideas concerning comprehensive park planning and its relationship to city growth and politics; it is primarily in these park reports that the main expression of his landscape ideas can be found.

Olmsted Brothers {John Charles Olmsted}. Report of Olmsted Brothers on a Proposed Parkway System for Essex County, New Jersey. Newark, [1915]. An exploration of the classes of parkways, with particular consideration for automobile and electric railway travel, and methods of land taking and assessment for parkways.

Olmsted John C. “The True Purpose of a Large Public Park.” In American Park and Outdoor Art Association Proceedings, 1897–1904. First Report, 11–17. Olmsted’s justification of the reasons and special requirements for setting aside considerable acreage for parkland in urban areas.

*Taken from: Birnbaum, Charles A., FASLA, and Robin Karson, editors. Pioneers of American Landscape Design. New York: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000.

Additional Resources:

Greenscapes: Olmsted’s Pacific Northwest. Joan Hockaday. Pullman: Washington State University Press, 2009.